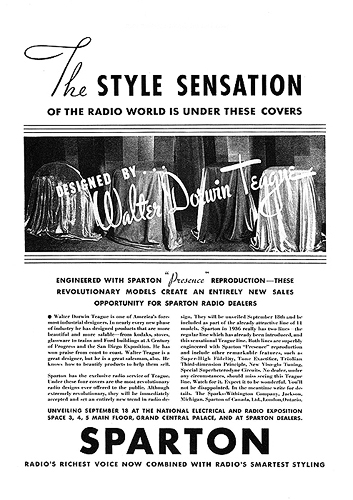

引用:

原帖由 LouisLee 於 3-6-2013 12:21 發表1902 年太陽能熱水器

Ada Mae, Pattie, and Nathan Stubblefield (l. to r.) with portable wireless telephone receiver, 1907

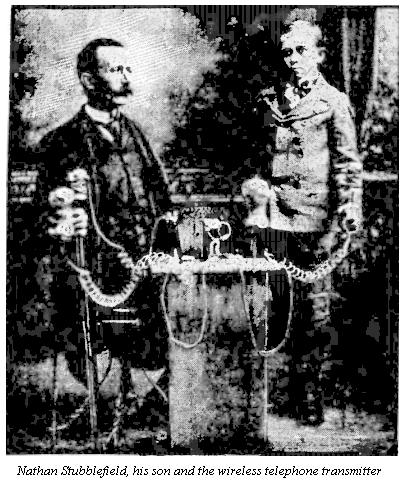

The latest and one of the most interesting systems of wireless communication with which experiments have recently been conducted is the invention of Nathan Stubblefield, of Murray, Ky., an electrical engineer who is the patentee of a number of devices both in this country and abroad. The Stubblefield system differs from that originated by = Marconi in that utilization is made of the electrical currents of the earth instead of the ethereal waves employed by the Italian inventor, and which, by the way, it is now claimed, are less powerful and more susceptible to derangement by electrical disturbances than the currents found in the earth and water. In this new system, however, as in that formulated by Marconi, a series of vibrations is created, and what is known as the Hertzian electrical wave currents are used.

The key to the methods which form the basis of all

the systems of wireless telephony recently discovered--the fundamental

principles of wireless telephony, as it were--was discovered at

Cambridge, Mass., in 1877 by Prof. Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor

of the telephone system which bears his name. On the occasion mentioned

Prof. Bell was experimenting to ascertain how slight a ground connection

could be had with the telephone. Two pokers had been driven into the

ground about fifty feet apart, and to these were attached two wires

leading to an ordinary telephone receiver. Upon placing his ear to the

receiver, Prof. Bell was surprised to hear quite distinctly the ticking

of a clock, which after a time he was able to identify, by reason of

certain peculiarities in the ticking, as that of the electrical

timepiece at Cambridge University, the ground wire of which penetrated

the earth at a point more than half a mile distant.

Some five years later Prof. Bell made rather extensive experiments

along this same line of investigation at points on the Potomac River

near Washington, but these tests were far from satisfactory. It was

found on this occasion that musical sounds transmitted by the use of a

"buzzer" could be heard distinctly four miles distant, but little

success was attained in the matter of communicating the sound of the

human voice. Meanwhile Sir William Preece, of England, had undertaken

experimental study of the subject of wireless telephony, and during an

interval when cable communication between the Isle of Wight and the

mainland was suspended, succeeded in transmitting wireless messages to

Queen Victoria at Osborne by means of the earth and water electrical

currents.

Mr. Stubblefield's experiments with wireless

telephony dated from his invention of an earth cell several years ago.

This cell derived sufficient electrical energy from the ground in the

vicinity of the spot where it was buried to run a small motor

continuously for two months and six days without any attention whatever.

Indeed, the electrical current was powerful enough to run a clock and

several small pieces of machinery and to ring a large gong. Mr.

Stubblefield's first crude experiments looking to actual wireless

transmission of the sound of the human voice were made without ground

wires. Nevertheless, by means of a cumbersome and incomplete machine,

without an equipment of wires of any description, messages were

transmitted through a brick wall and several walls of lath and plaster.

As the development of the system progressed, the present method of

grounding the wires was adopted, in order to insure greater power in

transmission.

<>

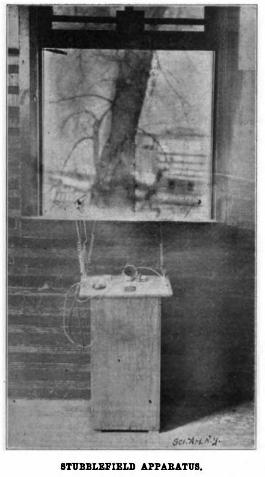

The apparatus which has been used in the most recent

demonstrations of the Stubblefield system, and which will be installed

by the Gordon Telephone Company, of Charleston, S. C., for the

establishment of telephonic communication between the city of Charleston

and the sea islands lying off the coast of South Carolina, consists

primarily of an ordinary receiver and transmitter and a pair of steel

rods with bell-shaped attachments which are driven into the ground to a

depth of several feet at any desired point, and which are connected by

twenty or thirty feet of wire to the electrical apparatus proper. This

latter consists of dry cells, a generator and an induction coil, and the

apparatus used in most of the experiments thus far made has been

incased in a box twelve inches in length, eight inches wide and eighteen

inches in height. This apparatus has demonstrated the capability of

sending out a gong signal as well as transmitting voice messages, and

this is, of course, of great importance in facilitating the opening of

communication.

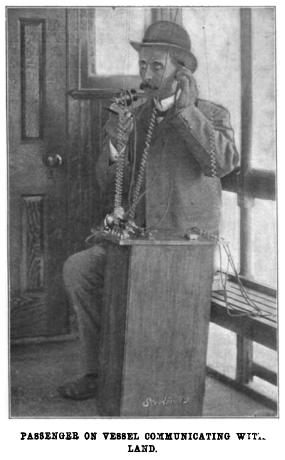

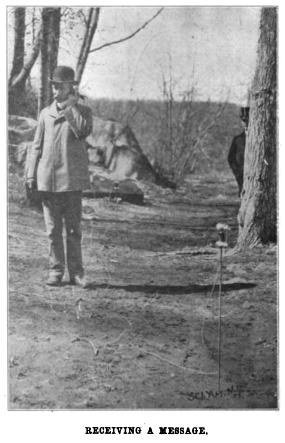

The most interesting tests of the Stubblefield system

have been made on the Potomac River near Washington. During the land

tests complete sentences, figures, and music were heard at a distance of

several hundred yards, and conversation was as distinct as by the

ordinary wire telephone. Persons, each carrying a receiver and

transmitter with two steel rods, walking about at some distance from the

stationary station were enabled to instantly open communication by

thrusting the rods into the ground at any point. An even more remarkable

test resulted in the maintenance of communication between a station on

shore and a steamer anchored several hundred feet from shore.

Communication between the steamer and shore was opened by dropping the

wires from the apparatus on board the vessel into the water at the stern

of the boat. The sounds of a harmonica played on shore were distinctly

heard in the three receivers attached to the apparatus on the steamer,

and singing, the sound of the human voice counting numerals, and

ordinary conversation were audible. In the first tests it was found that

conversation was not always distinct, but this defect was remedied by

the introduction of more powerful batteries. A very interesting feature

brought out during the tests mentioned was found in the capability of

this form of apparatus to send simultaneous messages from a central

distributing station over a very wide territory.

Extensive experiments in wireless telephony have also

been made by Prof. A. Frederick Collins, an electrical engineer of

Philadelphia, whose system differs only in minor details from that

introduced by Mr. Stubblefield. In the Collins system, instead of

utilizing steel rods, small zinc-wire screens are buried in the earth,

one at the sending and another at the receiving station. A single wire

connects the screen with the transmitting and receiving apparatus,

mounted on a tripod immediately over the shallow hole in which the

screen is stationed. With the Collins system communication has been

maintained between various parts of a large modern office building, and

messages have been transmitted without wires across the Delaware River

at Philadelphia, a distance of over a mile.

"I know that I have solved the problem of wireless telephony, and I will now devote myself to perfecting my apparatus. I want it to be perfect when given to the public, and it is my desire that it shall not appear with defects for the scientific journals to pick to pieces, my device it will be possible to communicate with hundreds of homes at the same time. A single message can be sent from a central station to all parts of the United States. I am confident that it will operate over long distances and even at great distances the transmitter will be no bulky instrument but quite small and convenient to handle. I think that my devices would be invaluable in the matter of sending out the United States weather bureau predictions, in directing the movements of a fleet at sea and in numerous ways which appeal to one at first thought. I am in hopes of getting a government appropriation to aid me in carrying on my work, or at least the promise of its adoption when perfected. The possibilities of the invention seen to be practically unlimited, and it will be no more than a matter of time when conversation over long distances between the great cities at the country will be carried on daily without wires. I intend to continue at work on my device and think that I will get other startling results in a short time."Stubblefield does not intimate at what time he will give out the diagrams of his apparatus. His workshop is in his home, which is located on a farm several miles from Murray and all of his preliminary experiments have been carried on with great secrecy on account of the comparative isolation of the place. He is quite as proud of the part which his boy has played in working on his apparatus as he is of the success of his public exhibition. He speaks entertainingly on the question of his invention and its possibilities.

"I certainly regard wireless telephony as possible just as much so as wireless telegraphy. In ordinary telephony no sound passes over the wire. Nothing but electric energy is transmitted. Now, instead of using a wire, the ether may be used, and the energy may be transmitted in the form of ether waves. The ether is the great vehicle for the transmission of energy. This medium fills all space, interplanetary and intermolecular. I further believe that this same ether is electricity and that all the electrical phenomena are due to the same disturbance of the ether. The ether is easily thrown into vibration, resulting in ether waves. There is an immense variety of these waves ranging from those whose lengths are only a few millionths of an inch to those whose lengths are hundreds of miles. Some of these waves affect the eye and are called light waves; some transmit heat energy. They are all electro-magnetic waves and all travel with immense velocity.Electricians here in discussing the problem go further into the matter than Stubblefield has for publication and say that as in wireless telegraphy, the receiving and sending instruments will probably have to be tuned electrically to one another and that by this means a wireless telephone communication might be had without fear of other people tapping the wireless line. Stubblefield thinks, that a transmitter for long distance will not have to be of large size, and in that event European and American houses, with properly tuned instruments, could hold daily conversations over wireless instruments no more cumbersome to the office than the first long distance telephone boxes.

"The manner in which these waves transmit energy may be illustrated in this way: suppose the pebbles on the shore of a pond of water are set in motion. This motion will disturb the water, cause waves to run across the pond, and, striking the pebbles on the farther shore, will put them in motion, the effect thus being like the cause. In a similar way the intermolecular vibration of the sun is transmitted to the earth through the agency of other waves and causes intermolecular vibration here. Now, we have this same principle in wireless telegraphy. At the transmitting station an electric current is made to oscillate under very high voltage or pressure, across a spark gap and with enormous frequency of vibration. The ether is violently disturbed at this gap and waves go out in every direction. These waves striking an electric circuit at a distant station, will set up oscillations in it similar to the oscillations which produced the waves. A telephone receiver will respond to these secondary vibrations, and so far we have wireless telephony. The principal thing at present, I think, is to devise a transmitter which can be operated by the voice. I do not know fully just what Stubblefield has accomplished, but the probabilities are that someone will develop a system of wireless telephony that can be used for practical purposes."

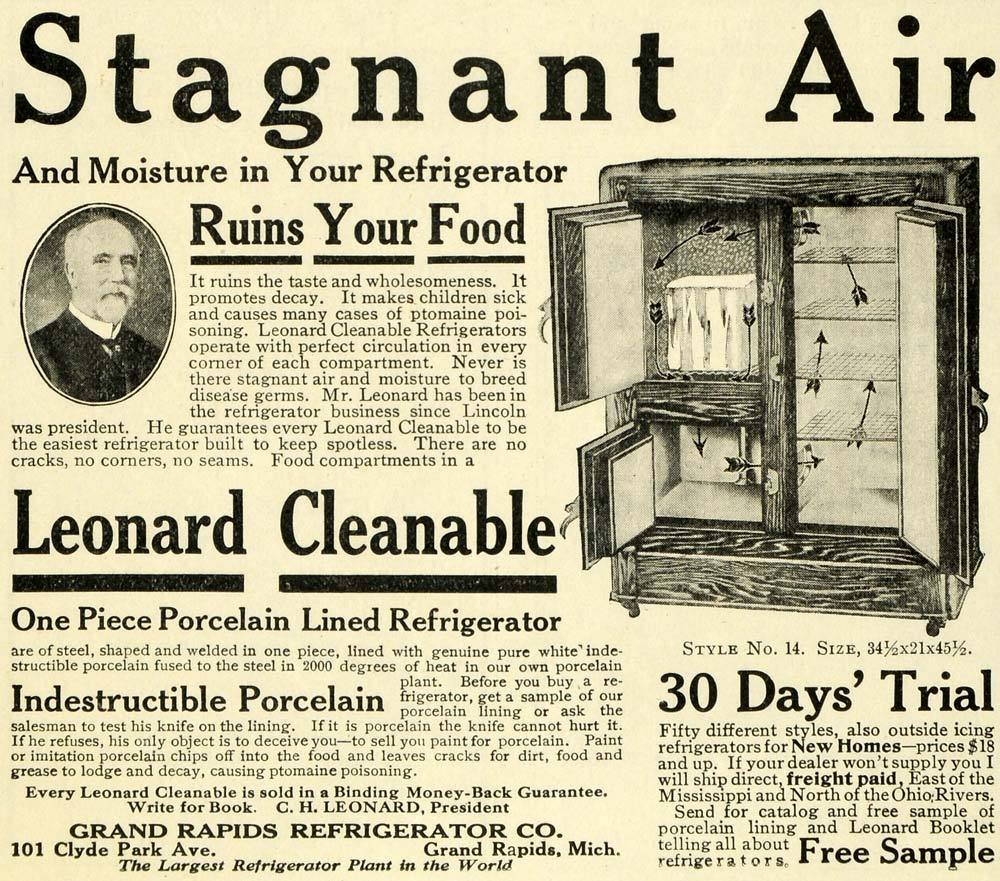

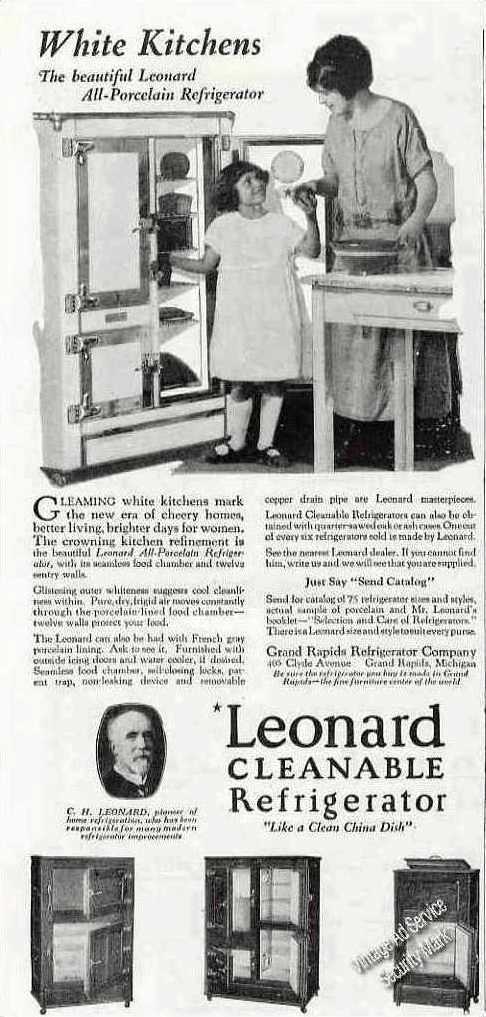

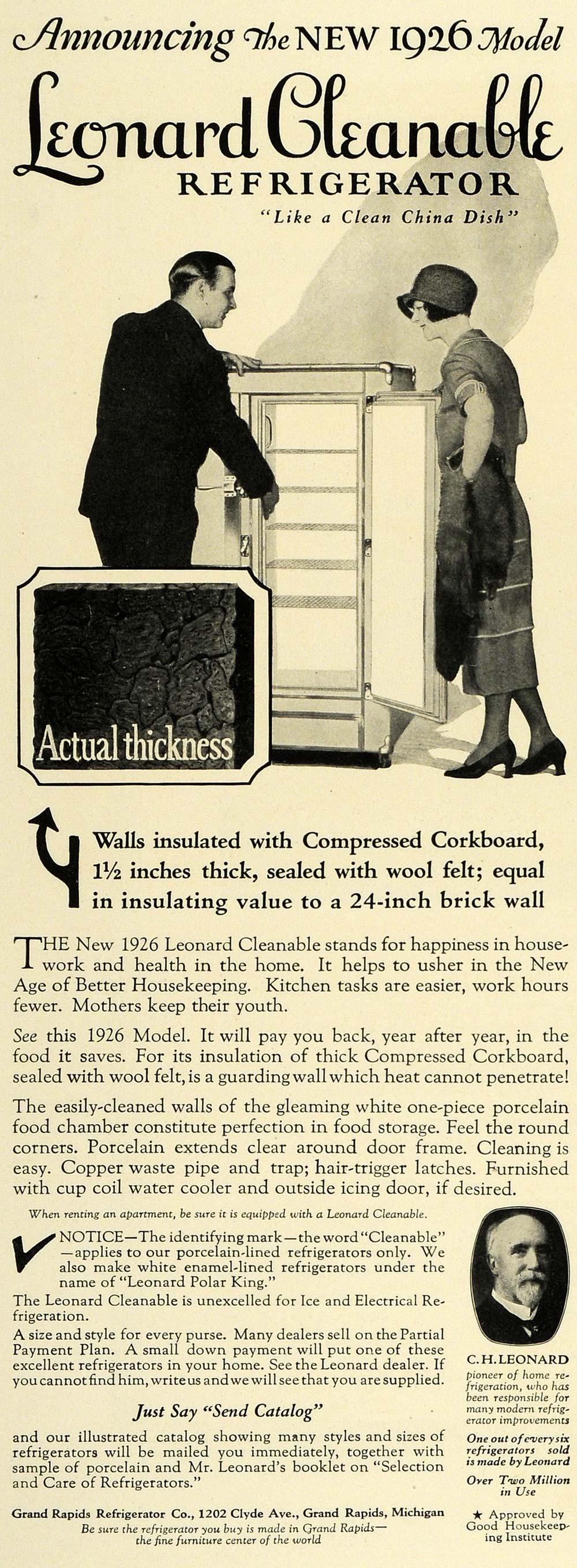

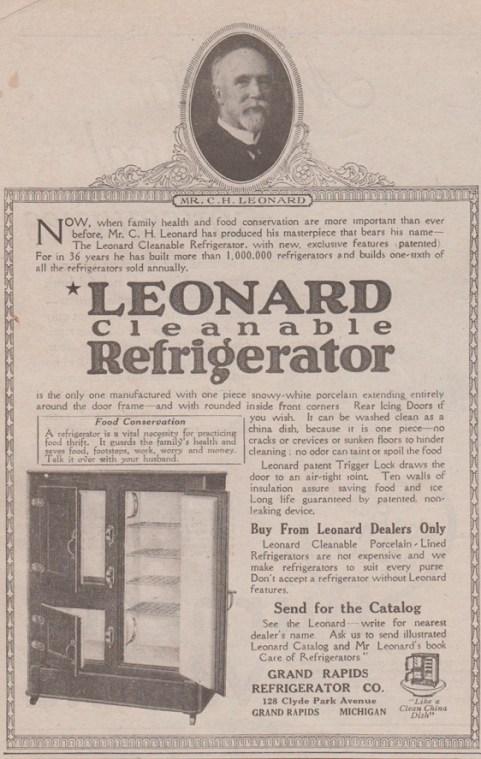

呢個雪櫃正! 夠classic!  藏x一流!

藏x一流!

看見這個古董雪櫃, 以為是件傢俬, 又似一個有腳的夾萬

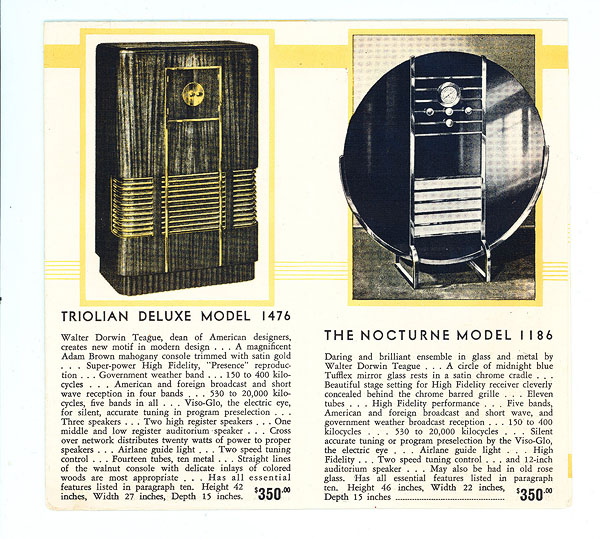

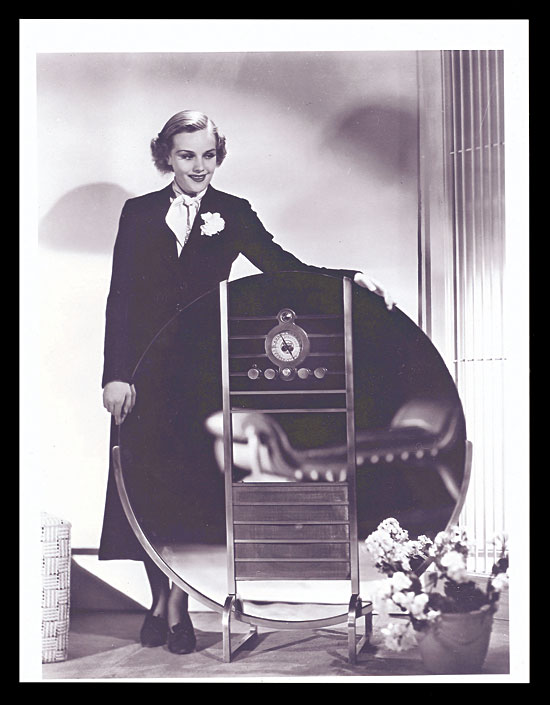

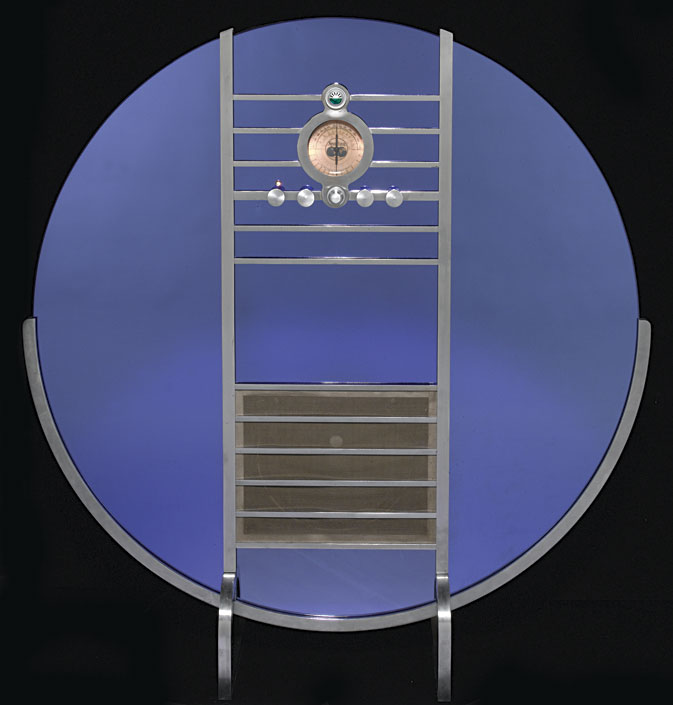

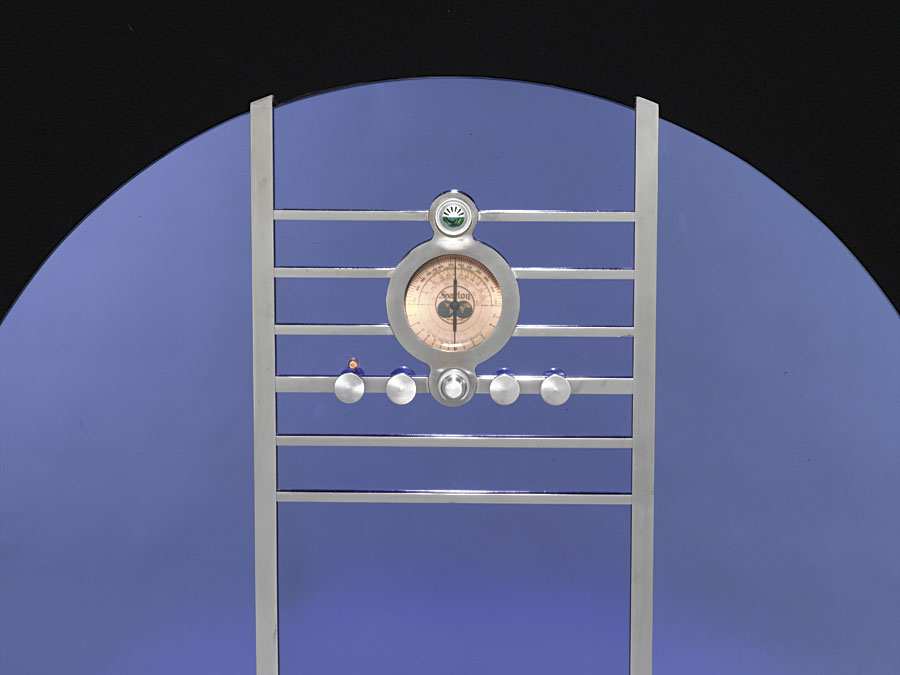

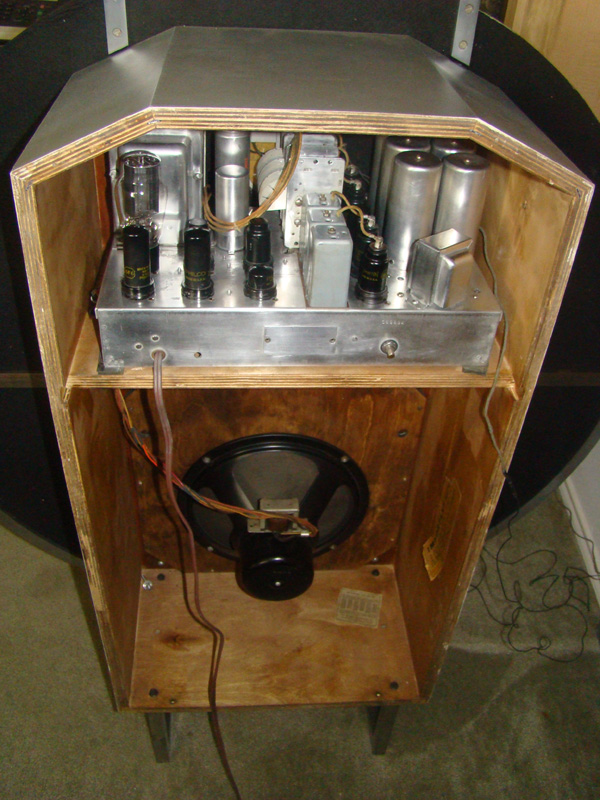

大型燈膽收音機, 認真大陣仗, 比一張摺檯還要大

| 歡迎光臨 經典日本特撮●動畫●卡通回憶 (http://oldcake.net./) | Powered by Discuz! 6.0.0 |